It affects the following diseases:

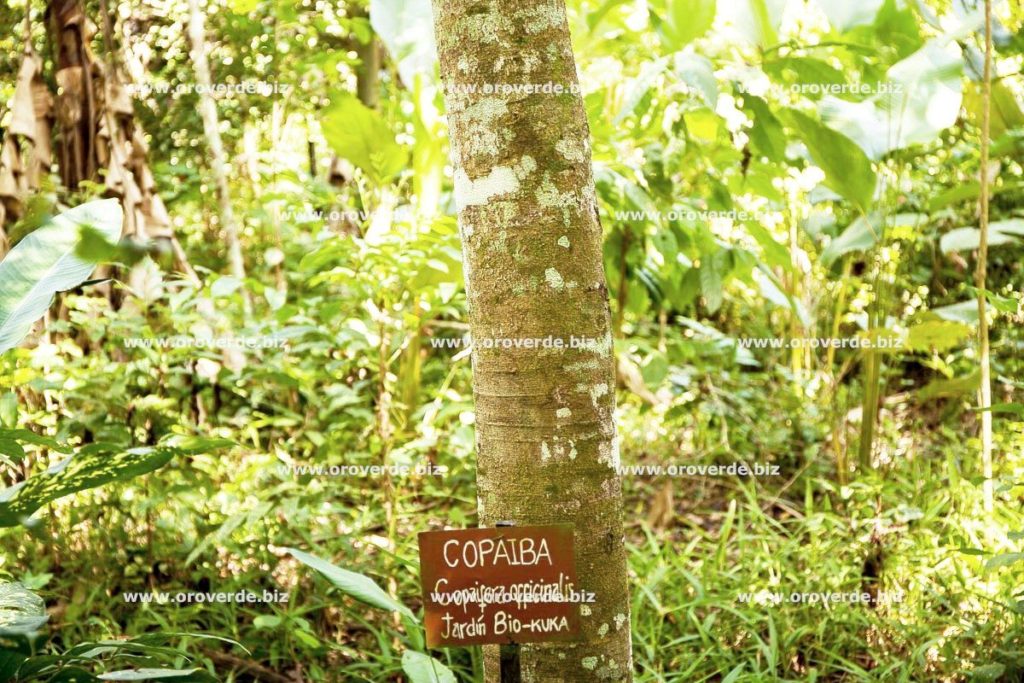

Family: Fabaceae

Genus: Copaifera

Species: officinalis L. (Linneaus ; 1762)

Native names:

Copper oil, balsam copaiba, básamo de copayba, cobeni, copaiba, copaiba-verdadeira, copaibeura-de-Minas, copaiva, copaipera, copal, cupayba, copauba, Jesuit’s balsam, Matidisguate, matisihuati, mal-dos-sete-dias pau-de-oleo.

Used part of the plant:

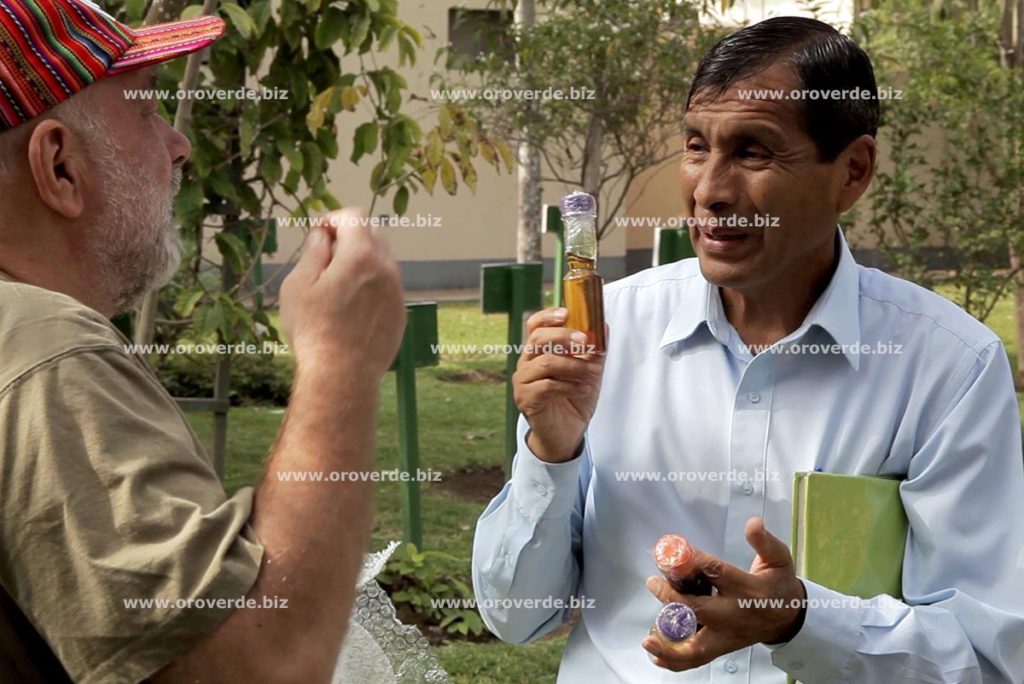

Resin (Resina copaiferae)

Indigenous use in traditional South American ethnomedicine in:

inflammation

bladder and urinary tract infections

gastric ulcers

sore throat, cough, tonsillitis, larynx and respiratory tract

skin injury

fungal nail diseases

in neoplastic diseases

hemorrhoids

psoriasis, leishmaniasis

constipation

Description:

Copaiba is an Amazonian heavily branched tree growing up to 30m high. The supportive, pinnate, oval-ovate leaves of smooth edges grow in the number of 5-7 on the basal stems. The inflorescence is a long lath composed of a large number of small white flowers. The fruit is an elongated pod with 2-4 seeds. The genus Copaifera includes 35 species occurring in the lowland rainforests of Central and especially South America (especially Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Guyana, Colombia, Peru and Venezuela). The traditional native ethnomedicine of the area uses mainly three species that are morphologically very similar: Copaifera langsdorffii is mostly found in cerrados of central Brazil, C. reticulata is the original Amazon region, and C. officinalis is abundant throughout South America, including the Amazon. All three types are used interchangeably. The part of the plant used in the ethnomedicine of native trunks is the resin, which is obtained by cutting or drilling a tree trunk (similarly to obtaining maple syrup). An adult can provide up to 40 liters of resin (sap).

In Brazilian ethnomedicine, the resin is used as a strong antiseptic and expectorant (promotes expectoration) and for calming the airways (including bronchitis and sinusitis), as well as a sedative and anti-inflammatory agent for urinary tract and bladder infections, or. kidney), as a diuretic (diuretic) and topical use to soothe skin inflammations. Herbal and pharmacies in Brazil commonly offer gelatin capsules with copaib resin, recommended for all types of internal inflammation (antiphlogistics), against stomach ulcers and cancer. The use of resin as a gargle for sore throat and tonsillitis (15 drops of resin in warm water) is also popular in Brazil. In contrast, traditional Peruvian ethnomedicine recommends three or four drops of resin mixed with a spoonful of honey for neck pain. Peruvian ethnomedicine also uses the resin for inflammation (antiphlogistics) and as a diuretic (diuretic), urinary incontinence, urinary problems, stomach ulcers, syphilis, tetanus, bronchitis, rhinitis, herpes, peritonitis and tuberculosis. It is used topically to stop bleeding and to moderate leishmaniasis (in the form of a compress).

Europe first encountered copaibic resin in 1625, when the Jesuits were imported from the New World to Spain, where it was subsequently used in the treatment of chronic cystitis, bronchitis, chronic diarrhea and as a topical preparation for hemorrhoids. In the United States, between 1820 and 1910, it was listed as a pharmacopoeial drug (Pharmocopoea), as a disinfectant, diuretic, laxative, and stimulant.

The validity of frequent empirical traditional uses is supported by numerous recent studies. Animal study conducted in 2002 by researchers in Brazil Prolonged external and internal use of the resin showed a high anti-inflammatory effect in the treatment of laboratory-induced inflammation. The group of substances called sesquiterpenes is responsible for this effect, especially the substance from this group called caryophyllene. However, the study revealed a high variability in the content of these sesquiterpenes in individual resin samples, in the range of 30-90%. Significant differences were recorded not only between different species of the genus Copaifera, but also between individual individuals of the species. For caryophyllene, tests have shown analgesic, antiphlogistic, antifungal (topical use on nail fungus) gastroprotective and tonic. The gastroprotective effect of caryophyllene was documented as early as 1996, which fully confirms the legitimacy of its ethnomedical use for gastric ulcers. In this animal study, not only did caryophyllene show a significant anti-inflammatory effect without any damage to the gastric mucosa (most other NSAIDs caused stomach problems). The traditional use of resin as an antiseptic for sore throat, upper respiratory tract inflammation and urinary tract infections can be explained by antibacterial properties, which were documented in 1960 and 1970. Researchers again confirmed (in 2000 and 2002) that resin as a whole (and in particular, two of its diterpenes (copalic and kaurenic acid) showed antimicrobial activity against gram-positive bacteria in an in vitro study. Another study performed with rock acid showed selective antibacterial activity against gram-positive bacteria. Other recent studies and research have focused on the antitumor properties of resins. As early as 1994, researchers in Tokyo isolated six chemicals (clerodan diterpenes) and subsequently tested against cancer in mice to determine the antitumor effect.

The effect of one of the isolated substances, colavenol-1, was twice as strong in increasing the lifespan of mice with carcinomas (by 98%) than with standard 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) chemotherapy. The use of resin also increased the viability of mice by 82%, which was a significantly higher percentage than with 5-FU (46%). Also of interest is the fact that caryophyllene showed significantly higher antitumor activity in in vivo studies compared to in vitro studies. The Spanish research team also focused on the antitumor effects when documenting the antimicrobial effects of the resin. The team presented the results of another substance contained in the resin, the so-called methylcopalate. This substance showed in vitro activity against neoplastic cell lines of human lung cancer, human colon cancer, human melanoma and lymphoid neoplasm in mice. A study conducted in Brazil in 2002 demonstrated the ability of kaurenic acid to inhibit the growth of human leukemia cells by 95% and breast and colon cancer cells by 45% in vitro. In all indigenous ethnomedicines, the internal use of the resin is limited to very small doses; usually only 5-15 drops (approx. 0.5-1 ml) 1-3 times a day. In higher doses, as documented, the use of the resin causes nausea, vomiting, fever and an allergic reaction, the most common manifestation of which is a skin rash. The French dermatologist states that these side effects can also occur in sensitive individuals when the resin is applied topically to the skin. Despite this, the FDA has approved the use of resin in the United States as a food additive and is used in small amounts as a flavoring in food and beverages. It is also used in small doses in cosmetics. Today, in the United States, copal resin is mostly used as a fragrance ingredient in perfumes and cosmetics (including soap, bubble bath, cleansers, creams, and lotions) for its antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and emollient properties. When used prudently in small doses, the South American rainforest brings us another great natural remedy for stomach ulcers, inflammation of all kinds, fungal nail diseases and other potential for its documented antimicrobial, wound and anticancer effects.

Contraindication:

Cannot be used internally when planning a pregnancy, pregnancy or breast-feeding. In some people, when used internally in larger doses, it can irritate the mucous membranes and cause coughing. Resin can cause an allergic reaction in sensitive individuals, most often a rash. Must be taken sparingly! in the beginning only one drop at a time. Never exceed a dose higher than a small teaspoon (5 ml) when used internally! Overdose can cause an allergic reaction, nausea, vomiting, rash, abdominal pain, loss of balance.

Side effects:

See contraindications

Traditional ethnomedical treatment prescription:

1-max. 5 drops in a glass of water, max. 3 times a day.

You can find out more information on the pages about standard preparations of herbs.

Phytotherapeutic properties:

Analgesic, antimicrobial and selective antimicrobial (gram-positive bacteria), antiseptic, dermatic, gastroprotective, laxative, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer.

Phytochemical composition:

Sesquiterpenes (even more than 50% of the total content), diterpenes, and terpenic acids. These chemicals include caryophyllene, calamenene, copal, coipaiferic, copaiferol, hardwick and rock acids. The resin is the richest known natural source of caryophyllene, reaching up to 480,000 ppm.

The main chemicals found in copaiby resin include: α-bergamotene, trans-α-bergamotene, α-cubebenekalamenen, α -multijugenol, α -selinene, α -curcumene, β-bisabolene, β -cubebene, β -elemene, β – farnesene, β -humulene, β -muurolene, β -selinene, alloaromadendren, γ-cadinene, γ -elemene, γ -humulene, δ-cadinene, δ -elemen, cyperene, calamesen, carioazulene, caryophyllenes, copaene, and copaiferol-, copal-, copaib-, paracobib- and polyaltol- acids, collavol 1, marakaibobalsam, methyl copalate, among others.

Zdroj:

- BRACK, E.A., Diccionario enciclopedico de plantas utiles del Perú, CBC-Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos «Bartolomé de Las Casas», Cuzco, Perú, 1999, ISBN9972-691-21-0

- CAVALCANTI, B. C., et al. “Genotoxicity evaluation of kaurenoic acid, a bioactive diterpenoid present in Copaiba oil.” Food Chem. Toxicol. 2006; 44(3): 388-92.

- COSTA-LOTUFO, L. V., et al. “The cytotoxic and embryotoxic effects of kaurenoic acid, a diterpene isolated from Copaifera langsdorffi.” Toxicon. 2002; 40(8): 1231–34.

- de ALMEIDA ALVES, T. M., et al. “Biological screening of Brazilian medicinal plants.” Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2000; 95(3): 367–73.

- de LIMA SILVA, J., et al. “Effects of Copaifera langsdorffii Desf. on ischemia-reperfusion of randomized skin flaps in rats.” Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2009 Jan; 33(1): 104-9.

- dos SANTOS,j.r., H., et al. “Evaluation of native and exotic Brazilian plants for anticancer activity.” J Nat Med. 2010 Apr;64(2):231-8.

- FERNANDES, R. M., Contribuicao para o conhecimento do efito antiiinflamatorio e analgesico do balsamo de copaiba e alguns de seus constituintes quimicos. Thesis, 1986. Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

- GEMINI, F., et al. “GC-MS profiling of the phytochemical constituents of the oleoresin from Copaifera langsdorffii Desf. and a preliminary in vivo evaluation of its antipsoriatic effect.” Int J Pharm. 2012 Aug 20.

- GHELARDINI, C., et al. “Local anaesthetic activity of beta-caryophyllene.” Farmaco. 2001; 56(5-7): 387-9.

- GOMES, M., et al. “Antineoplasic activity of Copaifera multijuga oil and fractions against ascitic and solid Ehrlich tumor.” J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008 Sep; 119(1): 179-84.

- Gomes, N., “Antinociceptive activity of Amazonian Copaiba oils.” J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007 Feb; 109(3): 486-92.

- GOMES, N., et al. “Characterization of the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of fractions obtained from Copaifera multijugaHayne.” J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010 Jan 12.

- KOBAYASHI, C., et al. “Pharmacological evaluation of Copaifera multijuga oil in rats.” Pharm Biol. 2011 Mar;49(3):306-13.

- KRAUCHENCO, S., et al. “Three-dimensional structure of an unusual Kunitz (STI) type trypsin inhibitor from Copaifera langsdorffii.” Biochimie. 2004; 86(3): 167-72.

- LEANDRO, L., et al. “Chemistry and biological activities of terpenoids from copaiba (Copaifera spp.) oleoresins.” Molecules. 2012 Mar 30;17(4):3866-89.

- LEGAULT, J., et al. “Potentiating effect of beta-caryophyllene on anticancer activity of alpha-humulene, isocaryophyllene and paclitaxel.“J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2007 Dec; 59(12): 1643-7.

- LIMA, S. R., et al. “In vivo and in vitro studies on the anticancer activity of Copaifera multijuga Hayne and its fractions.” Phytother. Res. 2003 Nov; 17(9): 1048-53.

- OHSAKI, A., et al. “The isolation andin vivo potent antitumor activity of clerodane diterpenoids from the oleoresin of Brazilian medicinal plant Copaifera langsdorfii Desfon.” Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1994; 4: 2889–92.

- PAIVA, L., et al. “Anti-inflammatory effect of kaurenoic acid, a diterpene from Copaifera langsdorffi on acetic acid-induced colitis in rats.” Vascul. Pharmacol. 2002 Dec; 39(6):303-7.

- PALACIOS VACCARO, W.J., Plantas Medicinales Nativas del Peru, Concytec, Lima, Perú, 1997, ISBN 9972-50-002-1

- PIERI, F. et al. “Bacteriostatic effect of copaiba oil (Copaifera officinalis) against Streptococcus mutans.” Braz Dent J. 2012;23(1):36-8.

- ROGERIO, A., et al. “Preventive and therapeutic anti-inflammatory properties of the sesquiterpene alpha-humulene in experimental airways allergic inflammation.” Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009 Oct; 158(4): 1074-87.

- SANTOS, R., et al. “Antimicrobial activity of Amazonian oils against Paenibacillus species.” J Invertebr Pathol. 2012 Mar;109(3):265-8.

- SANTOS, A., et al. “Antimicrobial activity of Brazilian copaiba oils obtained from different species of the Copaifera genus.” Mem .Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2008 May; 103(3):277-81.

- TAYLOR, L. Herbal secrets of the rainforest, Prima Health a division of Prima publishing, CA, USA, 1998, ISBN 0-7615-1734-0

- TINCUSI, B. M., et al. “Antimicrobial terpenoids from the oleoresin of the Peruvian medicinal plant Copaifera paupera.” Planta Med. 2002; 68(9): 808–12.

- TUNDIS, R., et al. “In vitro cytotoxic effects of Senecio stabianus Lacaita (Asteraceae) on human cancer cell lines.” Nat. Prod. Res. 2009; 23(18): 1707-18.

- VELGA, Jr., V., et al. “Chemical composition and anti-inflammatory activity of copaiba oils from Copaifera cearensis Huber ex Ducke, Copaifera reticulata Ducke and Copaifera multijuga Hayne–a comparative study.” J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007 Jun; 112(2): 248-54.

- VELGA, V., et al. “Phytochemical and antioedematogenic studies of commercial copaiba oils available in Brazil.” Phytother. Res. 2001; 15(6): 476–80.